Introduction

The Delhi High Court (Court) recently ruled that all food business operators must make a complete disclosure of all components and measurements used in a food product. This should include information about whether the substances are derived from plants or animals. According to the Court, everyone should be entirely aware of what they consume. The order was issued in response to a plea filed by Ram Gaua Raksha Dal, a non-governmental organisation (Petitioner). The Petitioner contended that food products on the market are not clearly labelled as plant or animal-derived, in turn breaching the right of people who practise strict vegetarianism.

Background

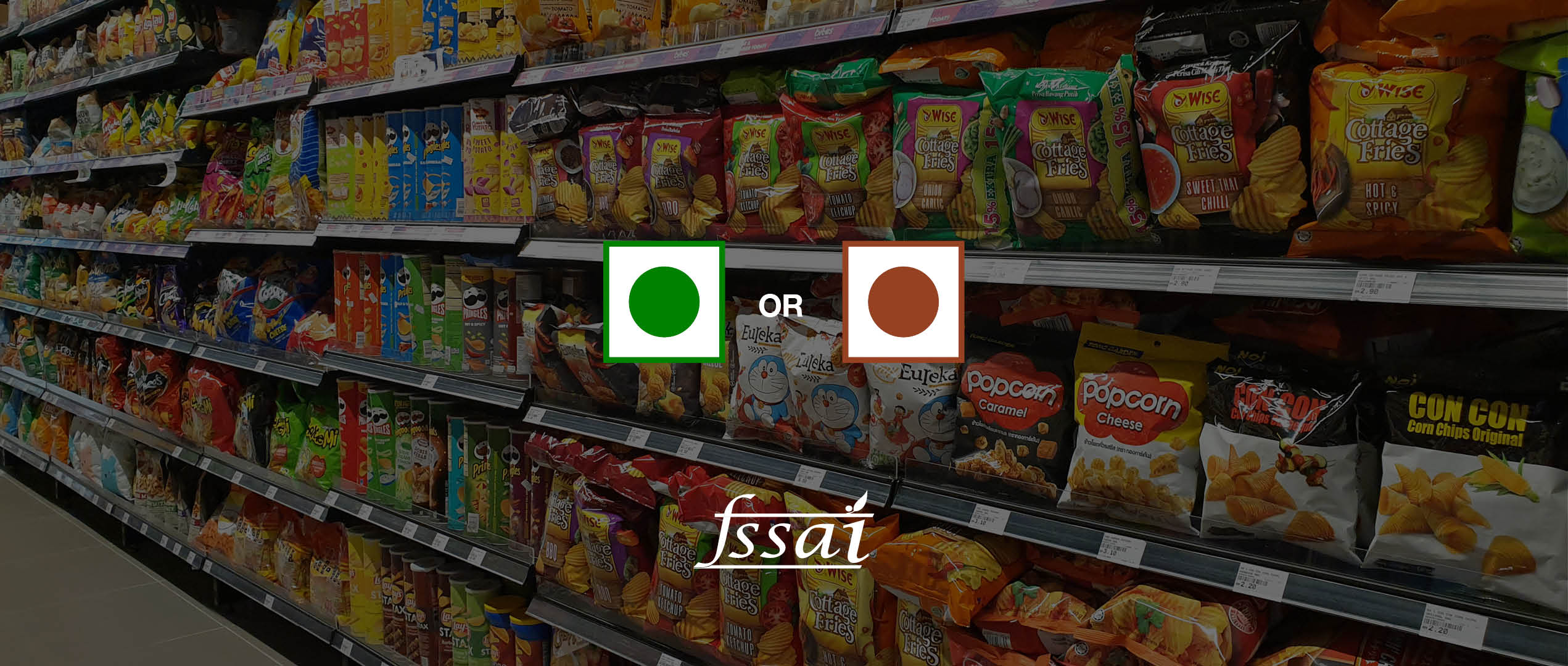

In India, packaged food and toothpaste must bear a mandated designation indicating whether they are vegetarian or non-vegetarian. This is in effect following the Food Safety and Standards (Packaging and Labelling) Act, 2006 (Act) and the Food Safety and Standards (Packaging and Labelling) Regulations, 2011 (Regulations). Vegetarian foods should be labelled with a green symbol, whereas non-vegetarian foods should be labelled with a brown symbol.

Non-Vegetarian Food is defined in Regulation 1.2.1(7) as an article of food that contains whole or part of any animal, including birds, freshwater or marine animals, or eggs or products of any animal origin, but excluding milk or milk products. Vegetarian Food is defined under Regulation 1.1.1(11) of the same Regulations as “any piece of food other than non-vegetarian food as specified in Regulation 1.1.1(7).” According to Regulation 2.2.2(2) of the aforementioned Regulations, all food business operators are obligated to include a list of substances used in the production or processing of food items.

The Petitioner’s point of contention was that the Regulations even mandated the disclosure of the fat’s source, namely if pork fat/lard, beef fat, or extracts thereof were utilized, but, in contrast, when it comes to the duty to make declarations for other ingredients, such as cheese and gum base, there was no requirement to specify the source of such substances used in the manufacture of the food article, such as cheese or gum base. Both cheese and gum can be made with vegetarian or non-vegetarian components.

The Petitioner submitted that the absence of an insistence under Regulation 2.2.2(2)(d) on the disclosure of any compound ingredients that account for less than 5% of the food (other than food additives) violates consumers’ rights, as they are kept in the dark about whether such compound ingredients are vegetarian or non-vegetarian. They asserted that the aforementioned ambiguity violates consumers’ Fundamental Rights under Articles 21, 19(1)(a), and 25 of the Constitution and impairs their ability to make informed choices.

Analysis by the Court

The Court concluded that certain food business operators appear to be exploiting – through a misreading of the Regulations – the fact that the Act does not specifically require food business operators to disclose the source of ingredients used in the compound ingredients that account for less than 5% of the food. The Petitioner had made the case for disodium inosinate, also known as E631, a food additive that is used in a variety of food treats such as instant noodles and potato chips but is frequently derived from meat, including fish and pigs. Taking note of the plea, a division bench comprising Justice Vipin Sanghi and Justice Jasmeet Singh directed that food business operators must adhere to food labelling standards or risk legal action.

The Court made it abundantly clear that the percentage of an ingredient, whether plant or animal-derived, used in the production of a food item was irrelevant, because even a trace of a non-vegetarian ingredient rendered the product non-vegetarian, offending the religious and cultural sensibilities or sentiments of strict vegetarians and interfering with their right to freely profess, practise, and propagate their religion and belief.

The Court imposed severe penalties on violators who abused the law by misunderstanding the restrictions. The Court observed that the labelling of ingredients in a food article, whether through the display of nutritional statistics or through the use of colour codes to distinguish between vegetarian and non-vegetarian foods, is inadequate under current food safety protocols. The Court declared that food business operators must provide detailed information about all ingredients in a food item, down to the source of each ingredient. The Court further stated that all individuals have a right to know what they are eating and that the public cannot be duped by a lack of information. Additionally, the Court noted that if food business operators fail to comply with the aforementioned standards, they risk being sued in a class action for infringement of the consuming public’s fundamental rights and facing punitive damages in addition to punishment.