The success of a business depends on various elements, including its brand. Commonly understood as just the name and logo, “brand” has a deeper meaning, incorporating many factors that feed into the consumer experience offered by the business. A successful brand strategy leverages brand identities to create imagery that prompts instant recall in consumers’ minds.

A brand’s identity consists of various elements and includes multi-sensory experiences as well. Logos, colours, names, and sounds are all part of a brand. For a brand identity to become an asset, it must be distinctive, and provoke an instant association with the business, product or service, distinguishable from the other brands in the market.

Sonic Identities

Of the various forms of brand identities, “sound” is increasingly being relied upon by marketers to gain recognition. Indian brands appear to have exponentially increased their investments in sonic branding over the past few years. Well-designed sonic cues are a valuable part of brand identity and can invite instant recall of brands (e.g., the Nokia ringtone). Naturally, these sonic cues must be accorded with adequate protection as well, as part of a larger strategy to secure the brand itself.

Legal Protection for Sonic Identities

Indian trademark law has expanded over the years to include various forms of marks into the definition of a trademark. The Indian Trade Marks Act, 1999 (“the Act”) defines “trade mark” as a mark capable of being represented graphically and distinguishing the subject goods and services from remaining proprietors in the market. Marks are divided into two categories, i.e., conventional (e.g., logos, brand names, and taglines) and non-conventional trademarks (e.g., sounds, colours, olfactory marks, and motion marks).

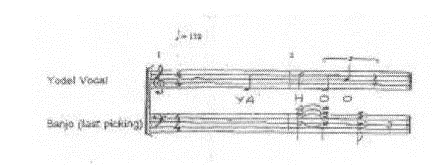

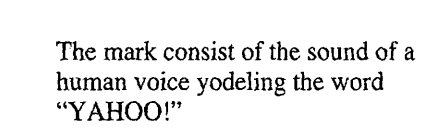

Sonic identities have been used by brand owners to market their products well before legal recognition was accorded to sound marks. The first sound to be protected as a trademark was the “NBC chimes” in the United States in 1947. In India, the first ever registration for a sound mark was in 2008, for Yahoo!’s yodel represented as a musical notation as well as a description of the sound.

(Application No. 1270407)

(Application No. 1270406)

Sound marks were formally recognised under law with the Trade Mark Rules, 2017 (“the Rules”), that have put into place a set procedure for registration of sound marks. As per Rule 26(5), the following conditions must be met when filing for a sound mark:

- The application must specify that the mark to be registered is a sound mark. If not specified, the application will be processed as a word/device mark;

- The application must contain a graphical representation of the sound in the form of musical notes; and

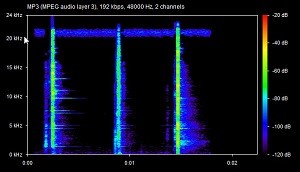

- The sound must be submitted in an MP3 format with no longer than 30 seconds in length.

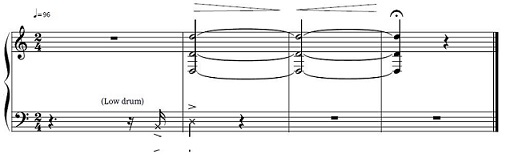

These rules streamlined the application procedure for protecting sound marks. By defining graphical representation for sound marks as musical notes, it removed confusion on the procedural and technical aspects. Various proprietors have since registered their distinctive sounds as trademarks, via representation of the sound as musical notes, including, recently, Netflix’s iconic “ta-dum” (5236448) and Zippo’s “sound of lighted opening, igniting and closing” (3995841):

(Netflix’s Application No. 5236448)

(Zippo’s Application No: 3995841)

Peculiarities of Sound Marks

Acquisition of Distinctiveness

With respect to non-conventional trademarks, distinctiveness is an essential requirement for registration. Certain sounds may encompass features of the products themselves, making them functional and non-distinctive. For example, a sound mark application for “V-twin engine” sound by Harley Davidson was denied by the USPTO as the sound was not inherently distinctive and depended majorly on the model of motorcycle. However, the “Piercing siren sound of federal signal corporation” by US Federal Signal Corporation was granted protection by the USPTO for its acquired distinctiveness. Such requirement of distinctiveness was emphasised again when the trademark application for the sound, “opening of a drink can” was rejected by the EUIPO, affirmed by the CJEU1, due to lack of distinctiveness and functional nature of the sound.

In India, too, for a sound mark to be fit for registration, the applicant must submit extensive evidence to substantiate distinctiveness of the mark. The draft Manual of Trade Marks Practice and Procedure, 2015 in the section on evidence of use for marks, provides that distinctiveness is an important consideration for the acceptability of sound mark, i.e., whether an average consumer perceives the sound as an indicator of the goods and services of a particular proprietor. No sound mark is prima facie registrable without ample evidence of factual and acquired distinctiveness. The Manual further lists certain kinds of sounds incapable of registration:

- Very simple pieces of music consisting only of only 1 or 2 notes;

- Songs commonly used as chimes:

- Well known popular music in respect of entertainment services, park services;

- Children’s nursery rhymes, for goods or services aimed at children;

- Music strongly associated with particular regions or countries for the type of goods/services originating from or provided in that area.

Graphical Representation

While the Rules attempted to streamline the application procedure for sound marks via a graphical representation of the musical notations, the ability of musical notations as an accurate representation is an important consideration. Musical notations may miss out on conveying important information regarding the sounds, such as pitch and duration. relying on western musical notation may also be inadequate to capture sounds based on music from other parts of the world. Such representation also limits the understandability of the description and caters only to music-literate audiences. Further, musical notes are limited to describing only musical sound, thereby removing a range of different types of marks from the potential sound trademarks. Musical notations also pose issues concerning trademark searchability, making it hard and impractical to search for sound marks in the register of trademarks.

Conclusion

The Indian trademark regime has attempted to bridge the gap between the growing use of sonic brand identities and protecting them via sound trademarks. But many practical difficulties remain that need to be addressed. Music notations may provide an appropriate way of representing musical marks, however, there is a need to establish an alternative method for graphical representation for non-musical sounds. For example, US trademark regulations also accept representations via oscillogram or sonogram. Similar requirements could be adopted in India in order to provide a wider coverage. Further, an option to provide written description of the sound may also be provided for further clarification. Lastly, in order to make trademark search for sound marks simpler, a separate database may be set up, with established rules to determine deceptive similarity between sound marks. Such a database would also be instrumental in keeping a watch on famous sounds being registered as a trademark by persons other than the actual owners, thus preventing trademark squatting.

1 Ardagh Metal Beverage Holdings GmbH & Co. KG v European Union Intellectual Property Office (T‑668/19)