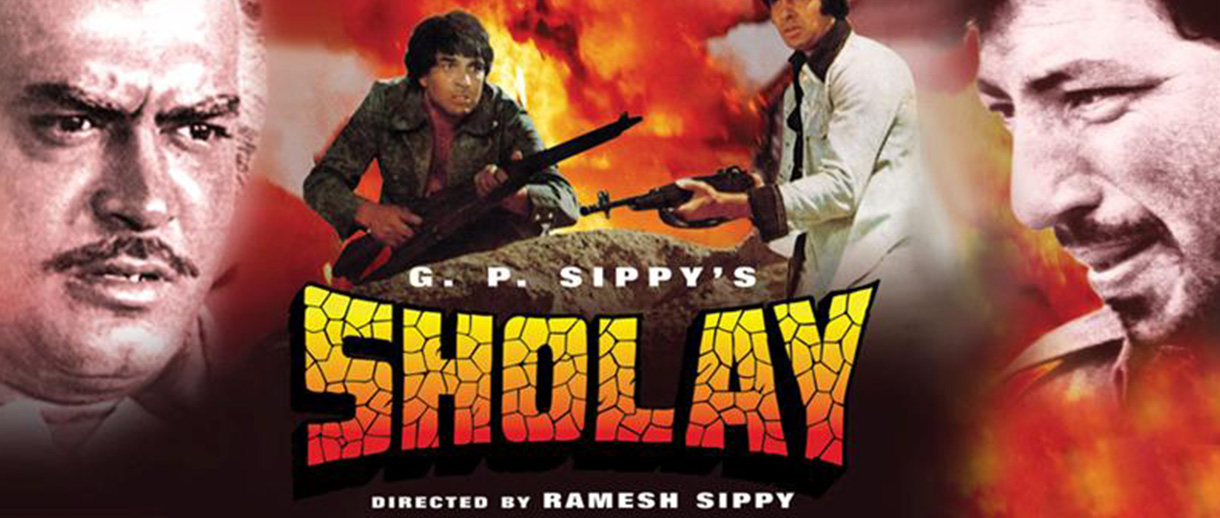

Cinema is a way of life in India, and the one film that epitomizes this national obsession is Sholay. Released nearly half a century ago, Sholay is a genre-defining film, whose appeal transcends all boundaries of geography, language, ideology, and class, and that established standards for what we now call “masala” blockbusters. With its iconic status and enduring popularity, the film has been, unsurprisingly, the subject of much litigation over the years. Recently, the Delhi High Court addressed the infrequently discussed rights and protections available to film titles in the context of this film.

The end of a 25-year-old debate

For a film like Sholay, the title remains important long after its release. Justice Pratibha M Singh of the Delhi High Court put to rest a twenty-year-long battle, describing the film as “a part of India’s heritage”, in Sholay Media Entertainemt and Anr. v. Yogesh Patel and Ors., CS (COMM) 8/2016.

This is not the first time that title rights in Sholay have been discussed in a court of law. In Sholay Media and Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. and Anr. v. Parag Sanghavi and Ors. (CS(OS) 1892/2006, Delhi High Court, 24 August 2015), ‘Sholay’ was declared as a “well-known” trademark. The court also held that copyright in the film vests in the producer, under Section 17 in the Copyright Act, 1957. It further held that the use of similar plot, characters as well as the use of the underlying music, lyrics, background score and even dialogues amounted to an infringement of the copyright in Sholay, and that the plaintiffs’ moral rights had been infringed due to the defendants’ distortion and mutilation of the original work.

In the present case, Sholay Media and Entertainment (P) Ltd. and Sippy Films (P) Ltd. (the plaintiffs) sued the defendants for using the film title in domain names (e.g., ‘www.sholay.com’), publishing a magazine using the word Sholay and putting up for sale various merchandise, exhibiting scenes and characters from the movie. The defendants had also filed an application for trademark registration in 1999 for the mark Sholay in both the United States and India. The plaintiffs sought a permanent injunction against the use of Sholay by the defendants, claiming that such use led to infringement, passing off, dilution and tarnishment of their well-known mark.

The defendants did not deny or dispute their use of Sholay and justified it on the following grounds:

- Film titles are not entitled to protection.

- They had applied for trademark registration earlier than the plaintiffs.

- There is no probability of confusion, because (i) the goods and services offered by both the parties are different and unrelated; and (ii) their website is on the internet, which is only accessed by educated people.

The law on film titles in India

Before getting into what the court actually said, a quick summary of the legal position on film titles is useful.

The intellectual property rights accorded to film titles is not always clearly spelt out in Indian statutes. The Indian Copyright Act, 1957 does not offer outright copyright to movie titles. The definition of ‘works’ in copyright law does not include movie titles. As laid down by the Supreme Court in Krishika Lulla & Ors. V. Shyam Vithalrao Devkatta & Anr. (2016) 2 SCC 521, film titles are not entitled for protection under the Copyright Act, 1957, as they lack the ‘minimum amount of authorship’ required for protection. The court reasoned that, as per Section 13, copyright subsists in original literary works, and film titles being incomplete in themselves, refer to the work that follows.

Protection for film titles is more commonly sought under the Trade Marks Act, 1999. Class 41 provides for registration of a mark used in connection with entertainment services. Besides Class 41, filmmakers also resort to ancillary classes associated especially with film merchandising, such as Class 09 (Cinematography films, vinyl records and audio tapes), Class 16 (promotional stationery), Class 25 (for clothing), and Class 35 (for advertising, marketing and publicity) and Class 42 (software, design and development of video).

Film industry associations, e.g., the Producers Guild of India, Indian Motion Picture Producers’ Association, and the Film Writers’ Association, also encourage registration of film titles, with a view to protect the commercial interests of films produced in India. Such registrations do not offer any statutory protection, but rights may be enforced by way of self-regulation.

The Delhi High Court 2022 decision

The court dismissed outright the claim that film titles were not entitled to trademark protection, holding that certain films cross the boundaries of just being ordinary words. ‘Sholay’, for example, was a mark associated exclusively with the film and the plaintiffs. Even if the plaintiffs had not registered it as a trademark, they would be entitled to protection under passing off law. For this, the court relied on Krishika Lulla & Ors. V. Shyam Vithalrao Devkatta & Anr. (2016) 2 SCC 521, wherein the Supreme Court said that “… no copyright subsists in the title of a literary work and a plaintiff or a complainant is not entitled to relief on such basis except in an action for passing off or in respect of a registered trade mark comprising such titles.” The court further relied on Kanungo Media (P) Ltd. v. RGV Film Factory & Ors. 2007 SCC OnLine Del 314, which recognized the applicability of principles of passing off under the Trade Marks Act on unregistered film titles, stating that, “In passing off, a necessary ingredient to be established is the likelihood of confusion and for establishing this ingredient it becomes necessary to prove that the title has acquired secondary meaning.” Thus, while a film title is entitled to protection under Trade Marks Act, in the case of unregistered titles, the test for a passing-off suit to be sustainable would require establishing that:

i. Secondary meaning has been accorded to the title; and

ii. There is a likelihood of confusion of source, affiliation, or connection on the part of the potential audience.

In Kanungo Media, the plaintiff had filed a suit of passing off against the use of the title Nishabd by the defendant for their upcoming film. Applying the test of secondary meaning, the court held that the plaintiff’s film, being a Bengali documentary, did not have the extent of viewership to have attained a secondary meaning, as opposed to a Hindi movie. The plaintiff had not registered the film title as a trademark, and had delayed in taking action against the defendant, who had already begun promotions for their upcoming film. As per the court, this delay led to acquiescence by the plaintiff.

In the present case, the court held that Sholay’s reputation as a film had already been judicially acknowledged, pointing to the Bombay High Court decision in Anil Kapoor Film Co. Pvt. Ltd. v. Make My Day Entertainment & Anr 2017 SCC OnLine Bom 8119. In this decision, Sholay was mentioned as having acquired a reputation such that the film title is uniquely associated with the film and no other. The Delhi High Court held that the film’s reputation was uncontroverted, thus according to the title a secondary meaning. Besides this, the plaintiffs had also registered Sholay as a trademark in several classes.

As regards the claim that the defendants’ application for trademark registration had come earlier, the court stated that Sholay was released in 1975, well before the registration and incorporation of the defendants’ company.

Regarding the contention of the defendants that there was no probability of confusion owing to a disparity of goods and services, the court stated that contents in a movie are no longer confined to the theatres. Movies have expanded to online and other platforms. The internet has created an additional market for movies. Sholay itself has also expanded to various markets and has several trade mark registrations in various classes. The activities undertaken by defendants would be covered by most of these registrations. Hence, the possibility of confusion that the goods and services of the defendants are offshoots of the movie is highly likely. Concerning internet usage, the court noted that the internet is now accessed by billions of users across the world. Given the fame and popularity of the film, it would be easy for any person, educated or illiterate, to establish a connection between the defendants’ website and the film Sholay.

In sum, the court granted a permanent injunction in favour of the plaintiffs, restraining the defendants from using the trademark Sholay. The court also awarded damages of INR 25,00,000/- (~USD 33,000), relatively rare in such cases, along with the direction to transfer all domain names incorporating the name Sholay or any deceptively similar variation thereof to the plaintiffs.

Conclusion

The 2022 Sholay decision reinforces the position that film titles are entitled not only to protection under trademark law, but also under common law by way of passing off. Trademark registration is not a prerequisite for being granted such protection. For a movie as famous as Sholay, it is not only the storyline that grabs the attention of the viewers, but over the years, the viewers have also started associating various elements of the production with the film. The film title gains the most attention and is the starting point of reference and recall for most. The judgement rightfully recognizes the efforts put in by the movie makers in acquiring this goodwill, such that the title becomes exclusively associated with the film and gains its own meaning altogether.